One of the first things you learn as a therapist is how to support a client with suicidal ideation. As part of the training curriculum, you gain an understanding of the key components of keeping clients safe. Straightaway, you learn how to not panic, how to be clear with communication, and how to stay calm when clients bring up this serious topic. How to support a client with suicidal ideation is an early part of training not only because of the consequences of not keeping clients safe, but because it’s almost guaranteed that it will come up at some point in your practice.

With death by suicide as the tenth leading cause of death in the US, clients of all backgrounds and therapeutic goals can be at risk — though, notably, certain minority populations, such as transgender individuals, face a greater rate of suicidal ideation and attempts.

Because of this, it’s important to be prepared to support your clients when the issue arises. We’ve put together this five step guide to supporting a client with suicidal ideation for reference when your client experiences a crisis.

1. Stay calm as you open the conversation

When a client discloses suicidal or self-harm ideation, they’re going out on a limb to alert you that something is very much wrong. It’s likely an incredibly scary time for them, and when they share with you the thoughts and feelings they’re having, they’re asking you for help. As part of their support system, it’s vital that you stay calm as you open the conversation further and offer them the assistance they need to stay safe.

The first step in calmly opening the conversation is to lead with empathy. As a therapist, responding to your client’s feelings from a heartfelt place of understanding likely comes naturally to you. However, it may be your instinct to take action right away to get them to a safe place. Doing this may cause your client to balk or shut down. For this reason, staying calm is vital for the success of the intervention.

When you react to your client’s suicidal ideation in a controlled, neutral way, it’s more likely that your client will also stay calm in the face of the situation. A controlled conversation gives them a sense of security in which to share more about their thoughts or the situation, which may be essential in supporting them through the crisis.

That said, it is also important to keep in mind the limits of confidentiality and to share with your client your ethical responsibilities as their therapist. While you may be afraid that your client will panic at hearing that you’ll need to report the conversation, stating this next step calmly and with compassion will help the client feel more comfortable with the idea.

2. Assess the level of risk

Once the conversation is opened from a place of empathy, you can ask more specific questions. By calmly asking for more detail, you’ll have the chance to assess the level of risk for your client. There are many excellent evidence-based risk assessments such as the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), or the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Depression (PHQ-9) scale. Having these assessments accessible gives you a straightforward way to measure the risk for your client. Some questions to include in your assessment include:

- Are you currently in a safe place?

- Have you ever tried to kill yourself previously?

- Do you have a plan?

- If you do have a plan, do you have a timeframe?

- Do you currently have access to a weapon or other means of self-harm?

When assessing this risk, keep in mind that there are a number of key factors to watch out for. This includes past suicide attempts, the intentionality of those attempts, and current access to firearms, weapons, or substances.

It may be difficult to assess the level of risk of the client without first building rapport and trust. If your client disclosed their ideation, that indicates that there is already a level of trust and comfort in the relationship. Using this baseline and by staying calm during the conversation, you’ll be able to gather the information you need to make a plan for next steps.

3. Consider protective factors, not only risk factors

While it’s crucial to assess the risk factors when assessing the situation, it’s also equally important to consider the client’s protective factors. Protective factors mitigate the impact of negative or harmful situations, conditions, or thoughts. It may be helpful to use the SHORES tool, a pneumonic, to generate a list of protective factors to lean on in times of crisis.

The SHORES tool includes:

- S: Skills and strategies. These are skills and strategies used to cope with negative thoughts or emotions, i.e. the client’s coping skills, techniques, or tools. This includes adaptive thinking or engaging in interests. An example would be mindful breathing, drawing in a coloring book, or calling a friend in times of negative emotion.

- H: Hope. When a client has hope for the future, they have something to look forward to. This includes any plans, goals, or dreams that have next steps to take. An example would be an upcoming vacation to Hawaii or a birthday celebration.

- O: Objections. Clients who have moral or cultural objections to suicide or self-harm may need to reckon with these objections before putting their ideas into action. This protective factor places a barrier between the client and the action by way of a belief system. Many religions prohibit suicide, which may dissuade the client from attempting.

- R: Reasons to live/restricted means. This includes listing out the motives for staying alive. An example of a motive for staying alive would be to see their children grow up or not to upset their loved ones with their death. If there are reduced means to attempt suicide, that is also a protective factor. By limiting access to firearms, medications, poisons, or other means of suicide, it becomes much more challenging to attempt.

- E: Engaged care. By nature of the situation, if your client discloses suicidal ideation, there is a strong connection between your client and a mental health or medical professional. Relationships with other engaged care professions such as teachers, counselors, nurses, or physicians are also protective factors.

- S: Support. The last protective factor to consider includes all areas of support, including supportive social environments, friendships, and family relationships. This could look like a close-knit student group, a sports team, or a sibling.

Recognizing protective factors may seem like a strengths-based spin in a time of crisis, however these protective factors could also be the difference between safety and harm. They’re an effective tool to use in conversation with your client to remind them of the good in their lives and their innate strength.

4. Create a safety plan — not a contract for safety

Creating a safety plan is best done ahead of time, however, it can also be helpful for clients who are at a low risk for suicide or self-harm. If the client is not at imminent risk, you can create a safety plan, or a written set of instructions for when they feel overwhelmed with negative emotions.

This is different from a contract for safety or a no-suicide contract. In a contract for safety, the client agrees not to harm themselves, either verbally or through writing. This type of contract is proven to be ineffective at preventing people from self-harming or dying by suicide. Clients can say that they agree (usually with the goal of being discharged from care or to set their care team at ease), however that doesn’t always equate to a cessation of self-harm.

Safety planning, on the other hand, is a tool that gives the client many options to try out before they self-harm. It is meant to guide the client towards healthier behaviors, including reaching out for and securing help to stay safe.

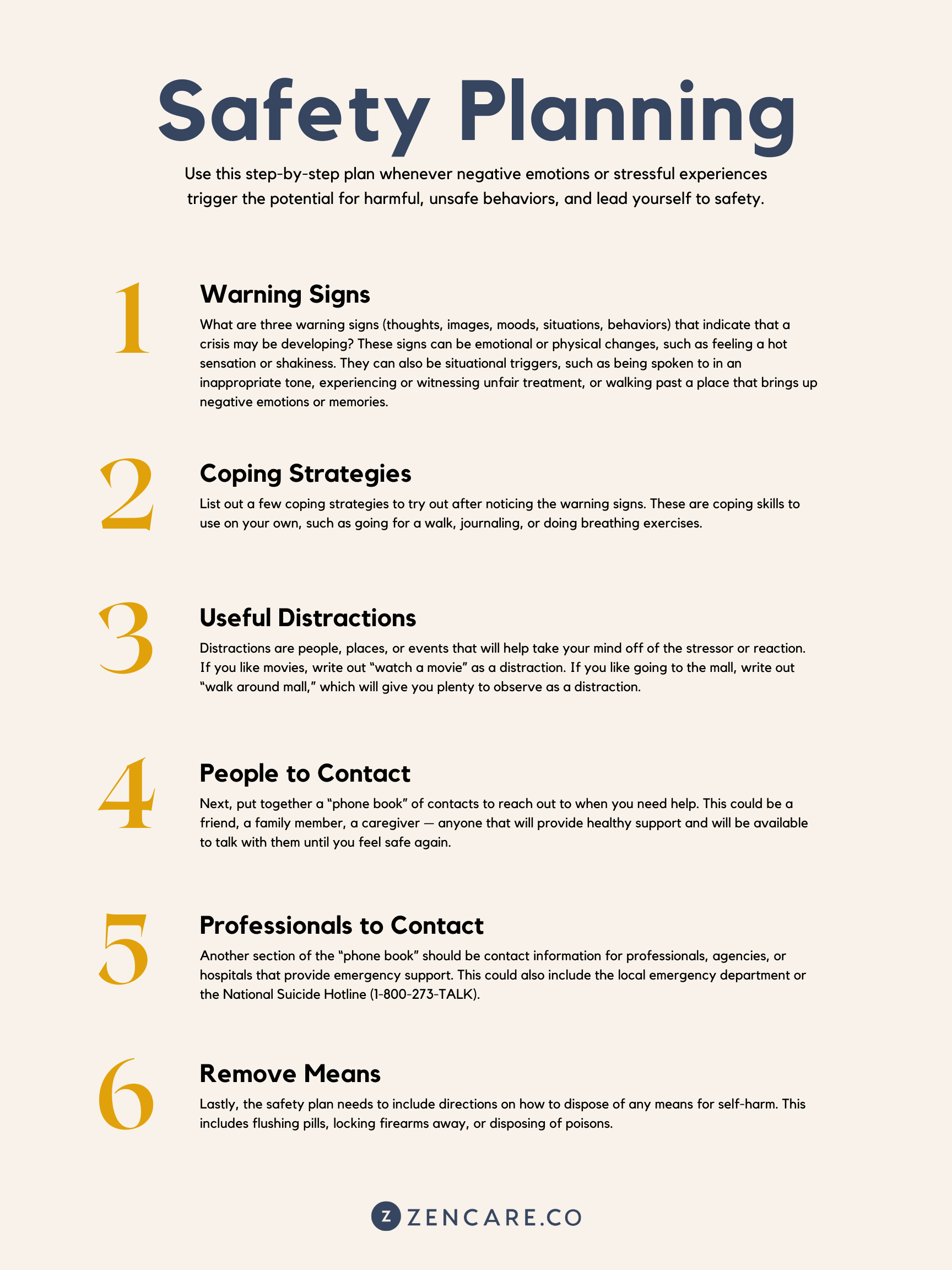

We’ve created a step-by-step guide for safety planning for you to use with your clients — download the template to get started. Here are a few tips when writing up a safety plan:

- Identify the warning signs: Determine what upsets your client and what could lead to the urge to self-harm or attempt suicide. This could include specific situations, locations, people, interactions, physical sensations, thought patterns, or feelings. An example could be when your client is spoken to in a condescending tone or witnesses unfair treatment.

- Identify internal coping strategies: List out a few coping strategies to try out after noticing the warning signs. These are coping skills to use on their own, such as going for a walk or lighting a candle.

- Identify useful distractions: If internal coping skills aren’t effective at helping your client manage their negative emotions, help them come up with a list of distractions. These are people, places, or events that will help them take their mind off of the stressor or their reaction. If they like movies, write out “watch a movie” as a distraction. If they like going to the mall, write out “walk around mall,” which will give them plenty to observe as a distraction.

- Identify people to contact: Next, help the client put together a “phone book” of contacts to reach out to when they need help. This could be a friend, a family member, a caregiver — anyone who will provide healthy support for the client and will be available to talk with them until they feel safe again.

- Identify professionals to contact: Another section of the “phone book” should be contact information for professionals, agencies, or hospitals that provide emergency support. This could also include the local emergency department or the National Suicide Hotline (1-800-273-TALK).

- Remove means: Lastly, the safety plan needs to include directions on how to dispose of any means for self-harm. This includes flushing pills, locking firearms away, or disposing of poisons.

By having a safety plan in place, your client will have explicit instructions to follow. Many clients, when in crisis, have difficulty figuring out what to do — a safety plan gives them their next steps towards reaching safety.

5. Continue to check in with your client

Once your client establishes safety, it becomes a top priority to continue to support your client even post-crisis. Having suicidal ideation is a terrifying experience, so your client may want to process through the experience with you in session. When appropriate, you might bring up what happened to trigger the ideation. You could also affirm the client’s strengths in overcoming the ideation or strategizing ways to handle ideation in the future. Your client may want to find the meaning of the experience or express what happened via journaling, painting, dancing, music — any way to process through their crisis and move forward.

Even if it’s been weeks since their crisis, touch base with your client to see how they’re feeling. It may also be productive to revise the safety plan every few months, especially if their situation changes or the resources available to them change.

Supporting a client with suicidal ideation can be exhausting for you, as the therapist, so it’s important to take care of yourself too. Your exhaustion comes from your compassion for your client and your dedication to their wellbeing. This is your own strength, as a therapist. Dive into your self care practice and remind yourself that you provided support for an individual in need — that’s no small feat!